Digital Financial Reporting

Why you should get to know xHTML and Inline XBRL

Digital Financial Reporting is the new phrase to come to terms with for European accountants, auditors, and IT departments, but what does it really mean?

The European Single Electronic Format (ESEF) reporting framework developed by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has been requesting Digital Reports for two years and around 5,000 companies across Europe have been preparing annual reports under its guidelines.

In addition, the EU is adopting the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which will mean that some 50,000 of the largest European companies will start formal Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting using a similar digital format over the coming years.

Of course, this is not new, the US SEC has required digital report submissions for over 10 years, as has the UK tax office, Japan, and a list of other global authorities. These reporting frameworks are all linked by the use of digital financial reporting formats, i.e., HTML rather than PDF, and key information tagging using the eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), which itself has been around for more than 20 years.

Digital transformation comes slowly to accounting, auditing, and market regulators, but its impact will be great. Is it working? Where are the obstacles so far?

This paper tries to analyse the progress and attempts to look further into the future to see how we can improve the experience.

The Benefits of standardisation

ESEF effectively mandates that all consolidated financial statements conforming to the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) should be rendered ‘machine-readable’ so that the key information they contain can be analysed readily by key stakeholders.

The expectation is that moving all corporate reporting to a standardised digital format will improve transparency and comparison across European capital markets. Adopting ‘data tagging’ using XBRL and embedding these in an HTML document, so that it can be read in any browser, removes the arduous and often error-stricken process of analysing large amounts of corporate financial information. The availability of such data will enable ‘crowd’ effects that improve the data quality of the information that enterprises report.

So, an investment analyst might want to ask, ‘What is the EPS of the largest 100 firms according to revenue in a specific industry or country’ and then ask ‘What are their share-based payment arrangements’. The analyst would need to find, download and open 100 PDFs, search for the EPS and notes on payment arrangements and extract the information manually. However, the XBRL data in digital reporting means she could run a report on an XBRL database, like UBPartner’s XT Database or use a service like Corporatings, and get the answer in seconds.

The Problem with PDF

PDF is an electronic format that enables content to be shared readily via email or website. Since its release in June 1993, it has become the ubiquitous output of choice for documents and printing, A key feature is that the content is unstructured and positioned relative to the page – which means that it is ideal for laying out text, images, headers/footers for printing, but difficult to identify tables and specific elements of the information it contains.

Compare this with HTML, the format of the web. HTML is focused on content and then applies rendering standards (CSS) so that it can work across all browsers in a standard way. In xHTML the content is highly structured, so tables, headers, sub-headers, text paragraphs, etc are easily recognisable.

XBRL simply adds ‘tags’ to numeric or text content to identify specific information that investors may be interested in. Inline XBRL embeds these tags in an xHTML document, so it is human readable, but machines can also extract and analyse the information that has been tagged.

Companies’ annual financial reporting processes have been based around print/PDF production for many years with established approval processes built around this, including management, finance, and internal and external auditors. Under the ESEF rules, software vendors have mostly converted PDF to HTML to tag the data with XBRL. However, converting a PDF to HTML has many issues because the converted HTML is poorly structured.

For example, an XBRL ‘block tag’ may be used on a piece of text, such as, the disclosure note on ‘share-based payment arrangements’. When the analyst extracts this content from PDF-converted XBRL data, it will often include unusable content (unintended code, rogue text or characters, unstructured tables, inconsistent spacing). This is a result of converting PDF to HTML.

The resulting report is also large, presenting an excessive data transfer, processing, analysis, and storage demand, which would be a fraction of the size, if the HTML were of a higher quality. With tens of thousands of filings per year, which will remain available on platforms for many years, this creates a significant cost and energy issue.

The solution is to start tagging using well-formed HTML. Creating this is a challenge for current software solutions and it does not give an easily printable document like a PDF, i.e., HTML gives no information about where a page starts or ends, no headers and footers, and offers no control for the printed format.

The transformation to Digital Reporting will bring new tools and processes for creating reports, and new approaches to reading them too. Companies which embrace this opportunity will see many benefits, to both their own data quality, content processes and reporting efficiency, but also for all stakeholders to access and analyse reporting and data in more usable ways.

Most companies now print very few reports, and no longer need to be held back by print-first processes and software. Companies which hold on to print-first PDF-led processes will miss the digital opportunity to significantly improve their reporting. PDF will still be useful for audiences, but PDF and print reports can now be a product of the digital process, not the centre of the process.

Inline XBRL: the perfect combination

Adding XBRL tags to an HTML document is the perfect answer to enable a human-readable, well-designed format that also identifies key information, often referred to as ‘material’ information in the context of financial information and accounting. Materiality is a fundamental concept in accounting and financial reporting because it helps determine what information needs to be disclosed or included in financial statements and what can be considered immaterial and thus excluded. By including standard IFRS or specific company tags in its financial reports, e.g., EPS in an ESEF report, a company is stating that the information is material.

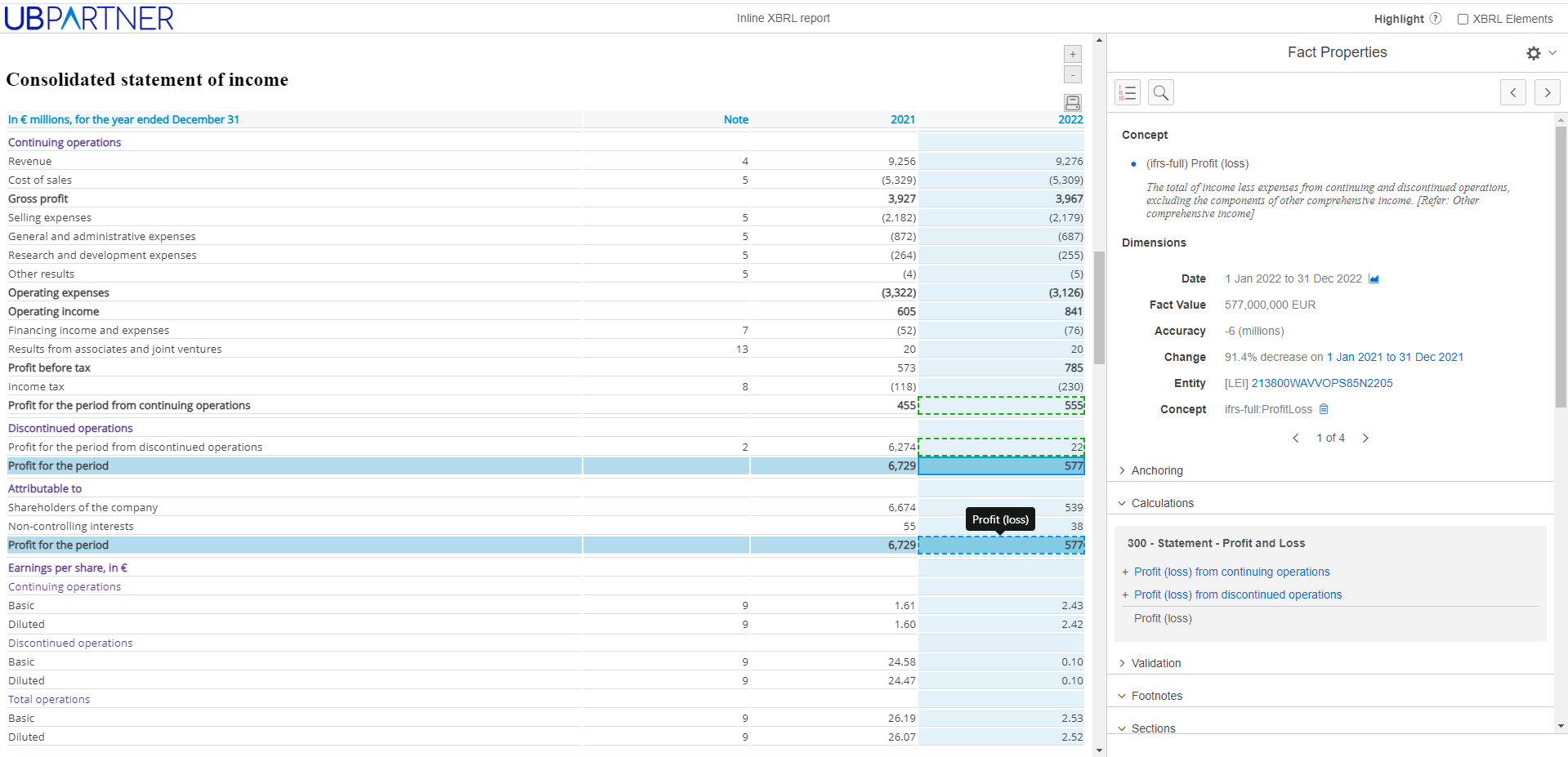

HTML also delivers a more interactive interface than PDF, e.g., embedded links to other content, interactive menus, etc. However, a special inline XBRL viewer is required for reviewing the document and the tags. This enables the document to be navigated in two ways via a standard contents list or by XBRL tags.

The tagged XBRL data can be validated against the model, as described in the ESEF XBRL taxonomy. This ensures that the information is of the right type – monetary, text; that repeated data (duplicates) are the same; and that hierarchies of monetary data, which make up the basic statements in financial reports add up.

The XBRL data and the rich semantics around it can be extracted and stored in an XBRL database so that it can deliver large-scale analysis and review without introducing further errors from manual ‘cut and paste’.

Content Management Systems

Modern websites are built using content management systems that enable the user to create and edit content, and then add this content to a web page (HTML). The content is styled using Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) to deliver high-quality visual experiences. Standardisation has meant that there are many tools to generate fantastic-looking websites without needing to understand code (HTML or CSS). However, a site can also be infinitely customised by expert coders as well.

Because its underlying format is XHTML (a highly structured form of HTML), the production of inline XBRL (iXBRL) will be best approached in the same way as websites, to deliver better quality and smaller HTML documents, which are also easier to tag content. This is known as ‘native XHTML’. i.e., created at source, not converted from another format, such as PDF. Native XHTML enables crucial content such as tables to flow directly from the financial consolidation system. The financial statement can be modelled in XBRL, and the data refreshed at any time, enabling the automation of processes that validate the financial data and prevent last-minute changes from upsetting the delivery timescales of an important report.

Modern iXBRL publishing tools such as ‘Pomdoc Pro’ and ‘Reportl’ are among the first to adopt this new approach. Providing more user-friendly, well-designed online reports, perfectly tagged, and with an easy-to-use, interactive interface. The best systems will also create the PDF version from the same content as the XHTML/XBRL.

ESEF Update Report

In 2021 and 2022, most reporting firms took the simplest available solution to ESEF and ‘bolted-on’ PDF tagging tools to their current processes, not realising its limitations or the digital opportunity that lies ahead. Gradually though, innovative reporters will see the advantages of moving to digital-first reporting.

So, what has been the result? As expected, it has not been perfect, but if you go to XBRL International’s (XII) XBRL Filings website you will find over 7,000 iXBRL reports ready to be reviewed and analysed. This is in itself a huge achievement for digital reporting.

Analysing these, our ESEF report card looks like this:

Basic formatting and packaging compliance: 9/10

- Most companies produced a properly packaged report including extension taxonomy and iXBRL document without too much fuss.

- Many would have found the exercise useful, in terms of establishing a baseline of what they are providing as an annual financial statement and why.

XBRL tagging: 6/10

- The simple and obvious tags on financial statements were mostly present.

- However, differences in local approaches and audit rules became clear. Using a standardised taxonomy is one thing, applying it and extending it in a standardised way is another.

- The use of company-specific tags (extensions) was always likely to create arguments. On one side you want comparability, but also want the company to be able to capture ‘material’ differences. The key issue is to remove needless extensions where a standard tag exists already.

Validation: 4/10

- Many vendors and issuers took issue with the ambiguity of the ESEF Filing manual and the consistency with the ESEF Compliance Suite. Vendors which followed the compliance suite closely pulled up many more errors than those that ignored awkward rules. This can be corrected with ease by ESMA and should be a priority.

- However, underlying this is a much bigger issue of modelling the financial data. To validate something, you need a model and rules by which to check it. Simple sign errors were prevalent just like in the US SEC, 10 years earlier. Missing calculations for totals and subtotals, missing hierarchies and concepts, and a lack of understanding of dimensions, all lead to numerous simple calculations errors.

- The use of ‘PDF conversion’ tools and a print-first ‘document’ approach to the process was probably the biggest culprit in delivering poor models.

- The author of the rules, ESMA, needs to more clearly express in the XBRL taxonomy and associated filing rules what is correct and what is not. This sounds easy, but there are competing views on keeping it loose vs hard rules that constrain company reporting. So, as in many of these frameworks a balance needs to be found based on what does and doesn’t work so far.

Usefulness: 2/10

- It is too early to expect more. 99.9% of reporting stakeholders do not yet understand or use the ESEF report. The software for iXBRL is immature and we only have two years of data.

- The basic validation issue above is always a problem in the early stages of an XBRL implementation but it can be minimised by carefully considered and well-tested rules.

- Authorities implementing rules without market consultation is always dangerous. In the second year, ESMA introduced ‘block tagging’ to ESEF. A badly conceived list of mandatory items was added to the Taxonomy, with no reference to the overall architecture of the IFRS taxonomy, and loose and poorly considered guidelines were added to the Reporting Manual without any market feedback being taken into account. The result was confusion and dissatisfaction among stakeholders.

- ESMA also appears to be ignoring the problems caused by PDF conversions, for now. However, this cannot last as the databases of ESEF reports are building up a history of unusable, poorly formatted data. Setting a reasonable timeline for requiring high-quality XHTML would solve this and improve software ready for the CSRD requirements.

The result is a mixed scorecard, typical of a new reporting framework and relatively easy to fix with the right approach and attitude. ESMA and the UK FCA/FRC, which incorporates ESEF into its UKSEF taxonomy, need to keep up the work on improving the framework. The US SEC reporting framework waited some 10 years before a group of vendors and interested parties decided to create the Data Quality Committee (DQC) to develop guidance on uniform, consistent tagging of financial data and to clarify those specific circumstances where custom tags are appropriate. Ten years is too long to waste in business.

The key items of work, from a technical viewpoint are:

- Define the ESEF submission format to require a minimum of ‘well-formed HTML’ which the US already insists on. ESMA should move to this definition as quickly as possible, and ahead of CSRD, which is even more reliant on block tagging. It may cause issues for some vendors, but most will adapt.

- The XBRL specification on which ESEF is based must be kept up to date, even if the regulators want the framework to ‘settle’. In particular, the Technical Standards (ITS) need to be updated to include version 1.1 of the XBRL Calculation specifications so that tolerances are introduced into document validation, removing small calculation differences, and encouraging more firms to provide complete financial models.

- Avoid non-standard rules, e.g., create inter-period or inter-dimension validation rules by specially organising the presentation linkbase, to keep a fully standards-based approach.

- Improve the guidance on and implementation within the ESEF Taxonomy for the use of any mandatory elements. In particular, regarding the list of mandatory block-tags to avoid unnecessary multiple layers of tagging.

- Include sector-specific tags. The IFRS Foundation is now adding such tags to the IFRS taxonomy. This will reduce the need to create extension elements and improve comparability.

- Mandate the need for management and auditors to provide an electronic signature for their parts of the report to create a fully digital publication process.

ESMA and the UK FCA/FRC have a massive opportunity to encourage the move to high-quality digital reporting in Europe and to lay the best practice foundations, setting the standard to develop more reporting frameworks using this approach.

Leveraging Digital Opportunities

However, technical standards do not exist in isolation and, from a wider industry viewpoint, driving forward the digital transformation of reporting will require ‘pro-digital’ regulation and further standardisation, including:

- Changing regulations to make the iXBRL document the legal annual report, rather than PDF, as an example, is currently the case in the UK.

- Re-thinking the balance between comparability and entity-specific definitions. However, what does this mean for the accountant’s view of ‘materiality’?

- Develop a roadmap to move to partial or progressive detailed tagging within reports. Reporting more granular information helps investors see the company’s calculations more clearly, e.g., how the company has calculated totals. However, consideration should be given to the cost implications for the issuers and again a review is needed on what is ‘material’.

- Standardisation of external processes such as assurance and auditing, so that reviews of reports are consistent. Today there are various national interpretations and divergences; of which there is much to learn about from 3 years of ESEF publications. The role of the supervising authority is pivotal to promoting common practice where many local practices exist.

- Providing a central access point for public XBRL reports as the EU plans for European Single Access Point (ESAP) to enable the ‘crowd’ checking effects to come into force quickly. In addition, provide education to the potential users (investors and analysts) to be able to use the published data.

So, a pro-digital approach will mean facing up to several, very large challenges outside of the underlying technology. In particular, the implications for materiality are huge, however, standardisation tends to level costs for preparers, auditors, and investors.

Note – the AI hype phase is in full flow and some writers say that using Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools could eliminate the need for expensive data tagging as AI can pick out the key information. However, any analysis tool including AI will benefit from the semantic relationships and structure provided by an XBRL taxonomy. In addition, it enables the company to identify exactly which information it wants to provide to satisfy financial guidelines. As the IASB says ‘In contrast, AI, in effect, makes educated guesses about common items’. Once tagged data is available and extracted into an XBRL database, AI tools can then be applied for data analysis and potentially find key supervisory relationships in the data that help formulate future policies.

PDF Today, Digital Reporting in 2025?

For now, companies have kept their existing processes tied to print-first PDF design and the associated approval processes. However, as they become more aware of the limitations of PDF, and more familiar with the advantages of digital reporting, we believe that they will make the transition to digital.

The UK Financial Reporting Council has recommended that “Compliance teams should embrace the adoption of the new ESEF standard as an opportunity to take a leap forward in digitalising the business reporting process, rather than seeing the new ESMA regulation as a reporting burden”. We see digitalisation as an increasing move to the automation of business processes within a firm. The adoption of digital-first disclosure and publishing systems is already underway in larger companies.

This trend will increase to encompass smaller firms as processes are reporting frameworks are standardised. Expectations of digital functionality are increasing too – with many audiences expecting that digital reporting makes content as available and accessible as the web.

The new CSRD and ISSB Sustainability reporting requirements will enable firms to start afresh with a new reporting framework and iXBRL publishing tools from 2025 onwards. ESG reporting faces many years of development and evolving approaches. Getting the right information technology standards in place will greatly help the transformation.

If the regulatory standards required higher quality data and well-formed XHTML, vendors would adapt their software and services, and this would improve companies’ reporting. Regulators have a vital role to play, by thinking carefully about the requirements of each stage and seeking feedback from interested market players.

In a future article, we will discuss what these applications could look like, how the data flows might be automated, how the data could be analysed using data analytics tools and, of course, the impact of AI.

In short, forward-thinking businesses will see this change as a positive opportunity to get their reporting and data to fulfil compliance requirements, both now and in the future, and to ensure that data is always visible and available for analysis by those measuring its performance.

The authors are Rob Riche of Friend Studio, Thomas Verdin of Tesh-Advice and Martin DeVille of UBPartner.

Please send comments, corrections, and any alternative ideas to info@ubpartner.com.